Enter the Matrix: An Interview with Ken Isaacs

News from the Web

The highly individual practice of American architect and designer Ken Isaacs (born 1927, Peoria, Illinois) challenged conventional definitions of modernism through designs that sought radical solutions to the spatial and environmental challenges of modern life. Fueled by the optimism that defined the postwar period, Isaacs began working with the new forms and technologies offered by modernism and advances in science, at the same time shunning the consumer-laden values of the American dream. The result was a lifelong commitment to a populist form of architecture that, because of its low cost and ease of construction, allowed a broad range of publics to participate in the design process.

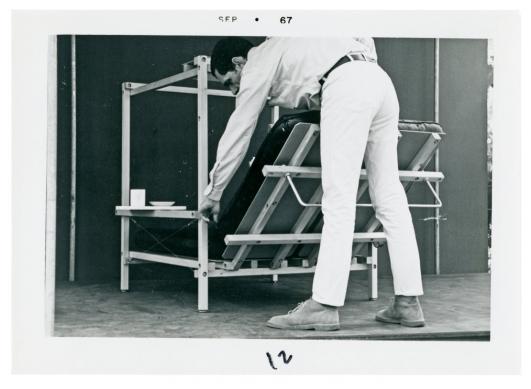

These designs, all founded on Isaacs’s concept of the matrix or total environment, were built using a three-dimensional grid and took the form of modular units called Living Structures that unified the multiple functions of furniture and home, including nomadic, sustainable architectural dwellings or Microhouses. Isaacs also applied his matrix idea to various multimedia information systems, most notably The Knowledge Box (1962), which was re-created by Isaacs in 2009, an experimental learning chamber that eschewed the traditional classroom for “environmental” concepts of education.

An early apprenticeship in mechanical engineering combined with studies in cultural anthropology and information theory shaped Isaacs’s early interest in architecture and design. He developed his Matrix Research Project while a graduate student at Cranbrook Academy of Art in the early 1950s, where he also created his first Living Structure (1954) and later taught his Matrix Study Course. Isaacs also held academic positions at the Rhode Island School of Design and the Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, where the original Knowledge Box was constructed. He is professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago, School of Architecture, where he taught architectural design and served for many years as director of graduate studies.

Isaacs’s work has achieved international acclaim and received considerable attention in both the popular press and within the media channels of the architecture and design communities. A prolific, prosaic, and opinionated writer, he is the author of several articles and two books: Culture Breakers, Alternatives and Other Numbers (1970), on his own design research, and How to Build Your Own Living Structures (1974), a DIY manual that details step-by-step instructions for building and adapting his constructions. He also served as a contributing editor for Popular Science from 1968 to 1972.

The following interview is a composite dialogue, a textual collage that combines passages from a conversation between Isaacs and myself that took place on September 9, 2014, in Granger, Indiana, and excerpts from the author’s own writings and other interviews. Revealed is an architect with a deep connection to the land of his Midwestern roots, and whose unwavering commitment to an experiential model of architecture, at once generative and generous, created a vernacular idiom of modernism that remains profoundly influential.

Susan Snodgrass: I’d like to begin with a quote from an article you wrote in 1967 for the publication Dot Zero: “The alpha chamber was a total environment or matrix designed to function as a culture-breaker.”

I see this statement, which is actually the first line of the article, as a manifesto of sorts, as the terms “alpha chamber,” “matrix,” and “culture-breaker” have come to define your practice. Can you unpack this statement?

Ken Isaacs: I like beginning like that. It really has a kind of beauty … [However,] my own descriptions of my work are very elusive and difficult.

I decided, in the late 1940s, to commit my energies to the development of alternatives. Not panaceas but new prototypical systems in architecture, living equipment, fabricating means and communications. The “buildings” and “furniture” of the old culture displayed a truly dazzling array of insufficiencies but the most arresting one was the fact that their value was predicated on their visible allegiance to value-saturated historical models.1

Snodgrass: So these new systems, whether architectural or informational, rejected (or “broke”) the middle-class cultural values that defined the American postwar period, with its emphasis on individualism, capitalist expansion, and material consumption.

Isaacs: Yes. The changes indicated that the mythic significance of the status symbol might eventually give way to the conception of the object as a useful tool with which to achieve a personal experiential result.

continue reading ar walkerart.org